History of Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| History of religions |

|---|

The history of Christianity begins with the ministry of Jesus, a Jewish teacher and healer who was crucified and died c. AD 30–33 in Jerusalem in the Roman province of Judea. Afterwards, his followers, a set of apocalyptic Jews, proclaimed him risen from the dead. Christianity began as a Jewish sect and remained so for centuries in some locations, diverging gradually from Judaism over doctrinal, social and historical differences. In spite of the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, the faith spread as a grassroots movement that became established by the third-century both in and outside the empire. New Testament texts were written and church government was loosely organized in its first centuries, though the biblical canon did not become official until 382.

Constantine the Great was the first Roman Emperor that converted to Christianity. In 313, he issued the Edict of Milan expressing tolerance for all religions. He did not make Christianity the state religion, but he did provide crucial support. Constantine called the first of seven ecumenical councils. By the Early Middle Ages, Eastern and Western Christianity had already begun to diverge, while missionary activities spread Christianity across Europe. Monks and nuns played a prominent role in establishing a Christendom that influenced every aspect of medieval life.

From the ninth-century into the twelfth, politicization and Christianization went hand-in-hand in developing East-Central Europe, influencing culture, language, literacy, and literature of Slavic countries and Russia. The Byzantine Empire was more prosperous than the Western Roman Empire, and Eastern Orthodoxy was influential, however, centuries of Islamic aggression and the Crusades negatively impacted Eastern Christianity. During the High Middle Ages, Eastern and Western Christianity had grown far enough apart that differences led to the East–West Schism of 1054. Temporary reunion was not achieved until the year before the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The fall of the Byzantine Empire put an end to the institutional Christian Church in the East as established under Constantine, though it survived in altered form.

Various catastrophic circumstances, combined with a growing criticism of the Catholic Church in the 1300–1500s, led to the Protestant Reformation and its related reform movements. Reform, and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, were followed by the European wars of religion, the development of modern political concepts of tolerance, and the Age of Enlightenment. Christianity also influenced the New World through its connection to colonialism, its part in the American Revolution, the dissolution of slavery in the west, and the long-term impact of Protestant missions.

In the twenty-first century, traditional Christianity has declined in the West, while new forms have developed and expanded throughout the world. Today, there are more than two billion Christians worldwide and Christianity has become the world's largest, and most widespread religion.[1][2] Within the last century, the centre of growth has shifted from West to East and from the North to the Global South becoming a global religion in the twenty-first century.[3][4][5][6]

Jesus of Nazareth c.27 - 30

[edit]

Early Christianity begins with the ministry of Jesus (c. 27–30)[7] Virtually all scholars of antiquity accept that Jesus was a historical figure.[8][9] According to Frances Young, "The crucifixion is the best-attested fact concerning Jesus."[10] He was a complex figure, which many see as a sage, a holy man, a prophet, a seer, or a visionary.[11] His followers believed that he was the Son of God, the Christ, a title in Greek for the Hebrew term mashiach (Messiah) meaning “the anointed one", who had been raised from the dead and exalted by God heralding the present and coming Kingdom of God.[12][13] As Young says, "The incarnation is what turns Jesus into the foundation of Christianity".[14] The church established these as its founding doctrines, with baptism and the celebration of the Eucharist (Jesus' Last Supper) as its two primary rituals.[15]

Early Historical background

[edit]

Christianity emerged in the Roman province of Judea during the first-century as an Apocalyptic sect within Second Temple Judaism.[12] The religious, social, and political climate was extremely diverse and characterized by socio-political turmoil. Judaism included numerous movements that were both religious and political.[12][16][17]

One of those movements was Jewish messianism out of which grew Jewish Christianity with its roots in Jewish apocalyptic literature.[18] Its prophecy and poetry promised a future anointed leader (messiah or king) from the Davidic line to resurrect the Israelite Kingdom of God and replace the foreign rulers.[12]

Jewish Christianity remained influential in Palestine, Syria, and Asia Minor into the second and third centuries.[19][20] Judaism and Christianity eventually diverged over disagreements about Jewish law, Jewish insurrections against Rome which Christians did not support, and the development of Rabbinic Judaism by the Pharisees, the sect which had rejected Jesus while he was alive.[21]

In its first three centuries, Christianity was largely tolerated by the Romans, though some saw it as a threat to "Romanness". This produced localized persecution by mobs and governors.[22][23] The first reference to persecution by a Roman Emperor is under Nero, probably in 64 AD, in the city of Rome. Scholars conjecture that the Apostles Peter and Paul were killed then.[24]

Apostolic Age (c. 30–100)

[edit]

The Apostolic Age began with the Great Commission (Matthew 28:16-20), included the Day of Pentecost, establishment of the early church community, early Christian persecution, and ended with the death of the last Apostle, believed to be John the Apostle. The first Christian communities were predominantly Jewish, although some also attracted God-fearers, Gentiles who visited Jewish synagogues.[25][26] Saul of Tarsus, a pharisee who became Paul the Apostle, persecuted the early Jewish Christians, then converted.[25] Paul made missionary journeys and wrote letters of instruction and admonishment to the churches.[25][27][28]

Developing church structure

[edit]According to Gerd Theissen, institutionalization began very early when itinerant preaching transformed into resident leadership in the first-century.[29] Edwin Judge argues that there must have been organization long before 325 since many bishops were established enough to participate in the Nicaean council.[30] Clement, a first-century bishop of Rome, refers to the leaders of the Corinthian church in his epistle to Corinthians as bishops and presbyters interchangeably. The New Testament writers also use the terms overseer and elders interchangeably and as synonyms.[31]

Early growth

[edit]Beginning with less than 1000 people, Christianity had grown to around one hundred small household churches consisting of an average of seventy members each, by the year 100.[32] It achieved critical mass in the years between 150 and 250 when it moved from fewer than 50,000 adherents to over a million. This provided enough adopters for its growth rate to be self-sustaining.[33][34]

Ante-Nicene period (100–312)

[edit]A more formal Church structure grew from the early communities, and various Christian doctrines developed. Christianity grew apart from Judaism in this period. The Ante-Nicene period saw the rise of Christian sects, cults, and movements. According to Carrington, the hierarchy of the post-Apostolic church developed at different times in different locations, with the overseers of urban Christian populations eventually assuming the social function of bishops.[31]

Sacred texts

[edit]The Hellenized Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria had produced the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, between the third and first centuries BC.[35] This was the translation of the Hebrew Bible used by first-century Christians.[36]

First-century Christian writings in Koine Greek, including Gospels containing accounts of Jesus's ministry, letters of Paul, and letters attributed to other early Christian leaders, had considerable authority even in the formative period.[37][38] The letters of the Apostle Paul sent to the early Christian communities in Rome, Greece, and Asia Minor were circulating in collected form by the end of the first-century.[39] By the early third-century, there existed a set of early Christian writings similar to the current New Testament,[40] though there were still disputes over the Epistle to the Hebrews, the Epistle of James, the First and Second Epistle of Peter, the First Epistle of John, and the Book of Revelation.[41][42] The canon was eventually settled based on common usage.[43]

By the fourth-century, unanimity was reached in the Latin Church on which texts should be included in the New Testament canon.[44] A list of accepted books was established by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by those of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397.[45] For Christians, these became the New Testament, and the Hebrew Scriptures became the Old Testament.[46] By the fifth-century, the Eastern Churches, with a few exceptions, had come to accept the Book of Revelation—and thus had come into harmony with the canon.[47]

The Gospels and other New Testament writings contain early creeds and hymns, as well as accounts of the Passion, the empty tomb, and Resurrection appearances.[48]

Early Christian art

[edit]

The early church fathers rejected the making of images.[49] This rejection, along with the necessity to hide Christian practice from persecution, left behind few early records.[50] What is most likely the oldest Christian art emerged on sarcophagi and in burial chambers in frescoes and statues sometime in the late second century to the early third century.[51][52] This art is symbolic, rising out of a reinterpretation of Jewish and pagan symbolism. Much of it is a fusion of Graeco-Roman style and Christian symbolism.[53][54] Jesus as the good shepherd is the most common image of this period.[55]

Persecutions and legalization

[edit]

In 250, the emperor Decius made it a capital offense to refuse to make sacrifices to Roman gods, resulting in widespread persecution of Christians.[56][57] Valerian pursued similar policies later that decade. The last and most severe official persecution, the Diocletianic Persecution, took place in 303–311.[58] There was periodic persecution of Christians by Persian Sassanian authorities, and the term Hellene became equated with pagan during this period.[59]

The Edict of Serdica was issued in 311 by the Roman Emperor Galerius, officially ending the persecution of Christians in the East. With the promulgation of the Edict of Milan in 313, in which co-emperors Constantine and Licinius legalized all religions, persecution of Christians by the Roman state ceased.[60]

The Kingdom of Armenia became the first country in the world to establish Christianity as its state religion when, in an event traditionally dated to 301, Gregory the Illuminator convinced Tiridates III, the King of Armenia, to convert to Christianity.

Spread of Christianity to c. 300 AD

[edit]

Driven by a universalist logic, Christianity has been, from its beginnings, a missionary faith with global aspirations.[62][63] It first spread through the Jewish diaspora[64][65] along the trade and travel routes followed by merchants, soldiers, and migrating tribes.[66][33][34]

In the first-century, it spread into Asia Minor (Athens, Corinth, Ephesus, and Pergamum).[67] Egyptian Christianity probably began in the first-century in Alexandria.[68] As it spread, Coptic Christianity, which survives into the modern era, developed.[69][70] Christianity in Antioch is mentioned in Paul's epistles.[71]

Early Christianity was in Gaul, North Africa, and the city of Rome.[72][73][74] It spread (in its Arian form) in the Germanic world during the latter part of the third-century, and probably reached Roman Britain by the third-century at the latest.[75][75]

From the earliest days, there was a Christian presence in Edessa (modern Turkey). It developed in Adiabene in the Parthian Empire in Persia (modern Iran). It developed in Georgia by the Black Sea, in Ethiopia, India, Nubia, South Arabia, Soqotra, Central Asia and China.

By the sixth-century, there is evidence of Christian communities in Sri Lanka and Tibet.[66][76]

Inclusivity, women and exclusivity

[edit]Early Christianity was open to both men and women, rich and poor, slave and free (Galatians 3:28). Baptism was free, and there were no fees, which made Christianity a substantially cheaper form of worship compared with the costly aristocratic models of patronage, temple building, and cult observances common in Greek and Roman religions.[77][78] An inclusive lack of uniformity among its members characterized groups formed by Paul.[79]

This inclusivity extended to women who comprised significant numbers of Christianity's earliest members.[80] Traditional social expectations of women in the Roman Empire did not encourage them to engage in the same activities as men of the same social class.[81] However, women were sometimes able to attain, through religious activities, a freedom otherwise denied to them.[82]

The Pauline epistles in the New Testament provide some of the earliest documentary sources of women as true missionary partners in the early Jesus movement.[83][84][note 1] Female figures in early Christian art are ubiquitous.[90] In the church rolls from the second-century, there is conclusive evidence of groups of women "exercising the office of widow".[91][92] Judith Lieu affirms that influential women were attracted to Christianity.[93] Much of the vociferous anti-Christian criticism of the early church was linked to "female initiative", which was seen as akin to sorcery, indicating women were playing a significant role.[81][94]

A key characteristic of these inclusive communities was their unique type of exclusivity.[95] Believing was the crucial and defining characteristic of membership, and "correct belief" was used to construct identity and establish social boundaries. Such belief set a "high boundary" that strongly excluded the "unbeliever" who was seen as still "in bondage to the Evil One".(2 Corinthians 6:1–18; 1 John 2: 15–18; Revelation 18: 4)[96][97][98] The exclusivity of Christian monotheism formed an important part of its success by enabling it to maintain its independence in a society that syncretized religion.[98] In Daniel Praet's view, exclusivity gave Christianity the powerful psychological attraction of elitism.[99]

Moral practices

[edit]Early Christianity's teachings on morality have been cited as a major factor in its growth.[100][101][note 2] Christians showed the poor great generosity, and according to professor of religion Steven C. Muir, this "was a significant factor" in the movement's early growth.[105] Early Christianity redefined family through their approach to death and burial by expanding the audience to include the extended Christian community.[106][107] Christians had no sacrificial cult, and this set them apart from Judaism and the pagan world.[108]

Late antiquity (313–476)

[edit]Historical overview

[edit]During late antiquity, the Christian faith spread throughout the Empire, into Western Europe, and around the Mediterranean basin.[30] The conversion of Constantine allied a monotheistic religion with a global power, both with ambitions of universality.[59] Yet, until the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (527–565), there was no Roman "Christian empire".[109] Law, literature, rituals, and institutions indicate that converting the empire to Christianity was a complex, long-term, slow-paced, and uneven process.[110][111][112]

In the fourth century, the existing network of diverse Christian communities became an organization that mirrored the structure of the Roman Empire.[113][114] Various doctrines developed that challenged tradition, Christian art and literature blossomed, and the church fathers wrote many influential works.[115][116][117]

In the late fourth century, Pope Damasus I commissioned Jerome to translate the Greek biblical texts into the Latin language used by the educated governing classes. Called the Vulgate, it uses many terms common to Roman jurisprudence.[118]

The Church of Late Antiquity was seen by its supporters as a universal church.[119][120] However, Patriarchs in the East frequently looked to the bishop of Rome to resolve disagreements for them resulting in an extension of papal power and influence.[115]

Constantine (c. 272 – 337)

[edit]

Constantine the Great became emperor in the West, declared himself a Christian, and in 313, just two years after the close of Diocletian's persecution, issued the Edict of Milan expressing tolerance for all religions.[121] The Edict was a pluralist policy, and throughout the Roman Empire of the fourth to sixth centuries, people shifted between a variety of religious groups in a kind of "religious marketplace".[122][123]

Constantine took important steps to support and protect Christianity.[124] He gave bishops judicial power and established equal footing for Christian clergy by granting them the same immunities polytheistic priests had long enjoyed.[125] By intervening in church disputes, he initiated a precedent for ecclesiastical councils.[126][127] Constantine devoted personal and public funds to building multiple churches, endowed his churches with wealth and lands, and provided revenue for their clergy and upkeep.[128] By the late fourth-century, there were churches in essentially all Roman cities.[129]

The state

[edit]

After Constantine removed restrictions on Christianity, emperor and bishop shared responsibility for maintaining relations with the divine.[130] Constantine and his successors, attempted to fit the Church into their political program.[131] Western church leaders resisted by making a case for a sphere of religious authority separate from state authority. Their objection forms the first clearly articulated limitation on the scope of a ruler’s power.[132]

Polytheism

[edit]Overt pagan-Christian religious conflict was once the dominant view of Late Antiquity.[133] Twenty-first-century scholarship indicates that, while hostile Christian actions toward pagans and their monuments did occur, violence was not a general phenomenon.[134][135][136] Jan N. Bremmer writes that "religious violence in Late Antiquity is mostly restricted to violent rhetoric".[137]

Under Constantine, non-Christians became subject to a variety of hostile and discriminatory imperial laws aimed at suppressing sacrifice and magic and closing temples that continued their use.[138] Blood sacrifice had been a central rite of virtually all religious groups in the pre-Christian Mediterranean, but it disappeared by the end of the fourth-century.[139] This is "one of the most significant religious developments of late antiquity," writes Scott Bradbury, and "must be attributed to ...imperial and episcopal hostility".[140]

Christian emperors wanted the empire to become a Christian empire, and they used empirical law to make it easier to be Christian and harder to be pagan.[141][142][143] However, there was no legislation forcing the conversion of pagans until the sixth-century, during the reign of the Eastern emperor Justinian I, when there was a shift from generalized legislation to actions that targeted individual centers of paganism.[144][145][146] Despite threatening imperial laws, occasional mob violence, and imperial confiscations of temple treasures, paganism remained widespread into the early fifth-century, continuing in parts of the empire into the seventh-century, and into the ninth-century in Greece.[147][148][note 3]

The Jews (395-398)

[edit]

Jews and Christians were both religious minorities, claiming the same inheritance, competing in a direct and sometimes violent clash.[153] Sporadic attacks against Jews by mobs, local leaders, and lower-level clergy occurred but did not have the support of church leaders due to a general acceptance of Augustine's teaching on the Jews.[154][155]

Augustine's ethic regarding the Jews rejected those who argued they should be killed or forcibly converted. Instead, he said Jews should be allowed to live in Christian societies and practice Judaism without interference because they preserved the teachings of the Old Testament and were "living witnesses" of the New.[154] According to Anna Sapir Abulafia, scholars agree that "with the marked exception of Visigothic Spain in the seventh-century, Jews in Latin Christendom lived relatively peacefully with their Christian neighbors" until the 1200s.[156][157]

Sometime before the fifth-century, the theology of supersessionism emerged, claiming that Christianity had displaced Judaism as God's chosen people.[158] Supersessionism was never official or universally held, but replacement theology has been part of Christian thought through much of history.[159][160] Many attribute the emergence of antisemitism to this doctrine, while others make a distinction between supersessionism and modern antisemitism.[161][162]

Orthodoxy and heresy

[edit]

Late Antique Christianity was dominated by its many conflicts defining and dealing with heresy and orthodoxy.[163][164][note 4] The sheer number of laws directed at heresy indicate it was a much higher priority than paganism for Christians in the fourth and fifth centuries.[167][168]

In addition to the traditionally accepted apostolic authority, the writings of church fathers and bishops such as Irenaeus and Ambrose, emerged as sources of authority on heresy and orthodoxy. The church fathers often condemned their opponents in a highly combative manner.[169] In these writings, heresy describes degrees of separation - "falling away", "estrangement", "alienation" - from the "true church".[166] Late antique communities defined their borders and secured their identities by confronting 'heresy' and 'heretics'.[170][171]

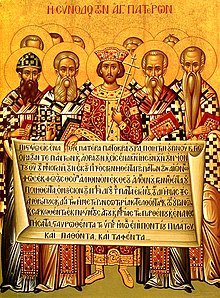

While there had been earlier disagreements with the Judaizers and the Gnostics, the first major heretical disagreement was between Arianism and orthodox trinitarianism over whether Jesus' divinity and the Father's divinity are equal.[26][172] The First Council of Nicaea (held in modern İznik, Turkey) called by Constantine in 325, and the First Council of Constantinople called by Theodosius I in 381, produced an affirmation of orthodoxy in the form of the Nicene Creed.[173][174]

East and West

[edit]By Late Antiquity, the tendency for East and West to grow apart was already becoming evident.[175] The Western church used Latin, while Eastern church leaders spoke and wrote in Greek, Syrian, and other languages which did not always include Latin. Theological differences were already becoming evident.[176][177][178] In the Roman West, the church condemned Roman culture as sinful, tried to keep them separate, and struggled to resist State control. In pointed contrast, Eastern Christianity acclaimed harmony with Greek culture and upheld unanimity between church and state.[179][180]

One particular bone of contention was Consantinople's claims of equal precedence with Rome.[120] Pentarchy, which shared government of the church between the Patriarchs of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and the Pope of Rome, was advocated by the legislation of the emperor Justinian, and was later confirmed by the Council in Trullo (692). The West opposed it, advocating instead for the papal supremacy of Rome.[181][182]

Ongoing theological controversies over Jesus' human and divine natures as either one (or two) separate (or unified) natures led to the Third (431), Fourth (451), Fifth (583) and Sixth ecumenical councils (680–681).[183] Schisms broke out after the Council of Chalcedon (451) wrote the Chalcedonian Definition that two separate natures of Christ form one ontological entity.[184][185] Disagreement led the Armenian, Assyrian, and Egyptian churches to withdraw from Catholicism, and instead, combine into what is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy, one of three major branches of Eastern Christianity, along with the Church of the East in Persia and Eastern Orthodoxy in Byzantium.[186][187][188]

Hospitals

[edit]

In Caesarea, monastics developed an unprecedented health care system that allowed the sick to be cared for in a special building at the monastery by those dedicated to their care. This gave the sick benefits which destigmatized illness, transformed health care, and led to the founding of a public hospital by Basil the Great in Caesarea in 369, the first of its kind, which became a model for hospitals thereafter.[189]

Antique art and literature

[edit]

Classical and Christian culture coexisted into the seventh-century, however, in the fourth-century, Constantine's sponsorship produced an exuberant burst of Christian art and architecture, frescoes, mosaics, and hieroglyphic-type drawings.[190]

A hybrid form of poetry written in traditional classic forms with Latin style and Christian concepts emerged. The Christian innovation of mixing genrés demonstrated the synthesis taking place in the broader culture, while new Christian methods of interpreting and explaining history began.[191][192][193]

The codex (the ancestor of modern books) was consistently used by Christians as early as the first-century. The church in Egypt had most likely invented the papyrus codex by the second-century.[194]

In the fourth and fifth centuries, church fathers wrote hundreds of texts from different traditions, cultural contexts, and languages (Greek, Latin, Syriac, Ethiopian, Armenian, Coptic, etc.) contributing to what is generally understood as the "Golden Age of Patristic" Christianity.[195] Augustine of Hippo, John Chrysostom, Gregory of Nyssa, Athanasius of Alexandria, Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus, Cyril of Alexandria, and Ambrose of Milan are among the many who made contributions to polemical works, orations, sermons, letters, poems, systematic treatises on Christian doctrine, Biblical exegesis, scriptural commentary, and legal commentary.[196]

Spread

[edit]Roman Africa province

[edit]

In North Africa during the reign of Constantine, Donatism, a Christian sect, developed. They refused - sometimes violently - to accept back into the Church those Catholics who had recanted their faith under persecution. After many appeals, the empire responded with force, and in 408 in his Letter 93, Augustine defended the government's action.[197][198] Augustine's authority on coercion was undisputed for over a millennium in Western Christianity, and according to Peter Brown, "it provided the theological foundation for the justification of medieval persecution".[199]

Britain and Ireland

[edit]The conversion of the Irish began in the early fifth-century through missionary activity and without coercion.[200] Christianity had become an established minority faith in some parts of Britain in the second-century.[201] In the fifth century, migration led Anglo-Saxon forms of Germanic paganism to largely displace Christianity in south-eastern Britain.[202] Irish missionaries went to Iona (563) and converted many Picts.[203] The Gregorian mission in 597 led to the conversion of the first Anglo-Saxon king Æthelberht around 600.[204]

Asia

[edit]There is no consensus on the origins of Christianity beyond Byzantium in Asia or East Africa. Though it is scattered throughout these areas by the fourth-century, there is little documentation and no complete record.[205] Asian and African Christians did not have access to structures of power, and their institutions developed without state support.[206] Asian Christianity never developed the social, intellectual, and political power of Byzantium or the Latin West.[66]

In 301, Armenia became the first country to adopt Christianity as its state religion. In an environment where the religious group was without cultural or political power, the merging of church and state is thought to represent ethnic identity.[207] In the fourth century, Asia Minor, and Georgia forged national identities by adopting Christianity as their state religion, as did Ethiopia and Eritrea. In 314, King Urnayr of Albania adopted Christianity as the state religion.[208][209][210][211][70]

Early Middle Ages (476–842)

[edit]Historical background

[edit]From the fourth to the sixth centuries, barbarian groups entered the Roman Empire. Many of them fought for Rome as allies then became disenchanted. Visigoths sacked Rome in 410, settled in southern Gaul by 418, and had taken over most of Spain by 484.[212] Alans, Vandals, and Sueves crossed the Rhine into Gaul and then Spain. Vandals took North Africa and were in turn conquered by Visigoths. Multiple barbarian groups set up separate kingdoms as attempts to establish a Western emperor failed.[213]

The new barbarian overlords were mostly Arian Christians.[214] Cities declined, and Europe became more rural, while Christianity provided unity and stability.[215][216] Monasteries became more important in the West, with Benedict founding his first monastery around 529 and writing the most famous of the "Rules" around 540.[212] By the 600s, the Franks rose to dominance in Gaul (modern France).[217][218][219] Clovis I was the first king to unite the Franks and convert to Catholicism.[214]

The Eastern Emperor Justinian I traveled west to retake territory lost to the barbarians. Initially successful, his campaign ultimately failed, resulting in the Eastern Empire's retrenchment.[220] They still had an emperor, towns thrived, and taxes were being collected, allowing Byzantium to become like a Middle Eastern state in the style of the Persian Empire.[221] In the late seventh-century, the Eastern Empire experienced plague and earthquakes, but it was primarily war (with the Sassanids, the Slavs, and Islam) that changed the Eastern Roman Empire into the independent Byzantine Empire.[222]

Three distinct cultures emerged from the geography of the former empire, in the same time period, between the 600s and 750: Germanic western Europe, Eastern Byzantium, and Islamic civilization.[223][224]

Christian growth, decline and the rise of Islam

[edit]In the early 600s, Christianity extended to the edge of Central Asia as far as Zerang and Qandahar in modern Afghanistan, and into the Sassanian Persian Empire, with Christian churches concentrated in northern Iraq in the foothills of the Zagros, and in the trading posts of the Persian Gulf.[217][218][219] Two main kinds of Christian communities had formed in Syria, Egypt, Persia, and Armenia: urban churches which upheld the Council of Chalcedon, and Nestorian churches which came from the desert monasteries.[225] Intense missionary activity between the fifth and eighth centuries led to eastern Iran, Arabia, central Asia, China, and the coasts of India and Indonesia adopting Nestorian Christianity. The rural areas of Upper Egypt were all Nestorian. Coptic missionaries spread the Nestorian faith up the Nile to Nubia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia.[226]

Born in the seventh century, Islamic civilization, in a series of Arabic military campaigns, and diplomacy, between 632 and 750, conquered much of Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persia, North Africa, and Spain.[227][228] By 635, many upper-class Christian refugees had moved further east to China at Hsian-fu.[229] Inferior legal status and persecution of non-Muslims eventually devastated the Chalcedonian churches in the cities. The monastic background of the Nestorians made their churches more remote, making them the most able to survive and cultivate new traditions.[230][231] A vibrant Asian Christianity with nineteen metropolitans (and eighty-five bishops), centred on Seleucia (just south of Baghdad), flourished in the eighth-century.[232][233]

Christianity became dominant in England throughout the 7th century, during which suppression of Germanic paganism began, with there being no recorded heathen kings after 954.[234][235][236][237]

The Franks preserved their Christian kingdom in the West, resisting Arabic inroads into southern France in 732.[238] Charlemagne began the first Medieval Renaissance, the Carolingian Renaissance, a period of intellectual and cultural revival, in the Frankish kingdom beginning in the 8th century and continuing throughout the 9th century.[239][240][241]

Christendom

[edit]

In Europe, the Early Middle Ages were diverse, yet the concept of Christendom was also pervasive and unifying.[242][note 5] Medieval writers and ordinary folk used the term to identify themselves, their religious culture, and even their civilization. Mixed within and at the edges of this largely Christian world, barbarian invasion, deportation, and neglect also produced large “unchurched” populations.[244][245][246] In these areas, Christianity was one religion among many and could combine with aspects of local paganism.[234][247] Early medieval religious culture included "worldliness and devotion, prayer and superstition", but its inner dynamic sprang from a commitment to Christendom.[242]

Education

[edit]

The means and methods of teaching a mostly illiterate populace included mystery plays (which had developed out of the mass), wall paintings, vernacular sermons and treatises, and saints' lives in epic form.[242] Christian motifs could function in non-Christian ways, while practices of non-Christian origin became endowed with Christian meaning.[248] From the sixth to the eighth centuries most schools were monastery-based.[249]

Law

[edit]Throughout this period, a symbiotic relationship existed between ecclesiastical institutions and civil governments. Canon law and secular law were connected and often overlapped.[250] Churches were dependent upon lay rulers, and it was those rulers - not the Pope - who determined who received what ecclesiastical job on their lands.[178][251][252]

Canon law enabled the church to sustain itself as an institution and wield social authority with the laity.[253] In the East, Roman law remained the tradition. After the Empire fell, the West was a world of relatively weak states, endowed aristocracies, and peasant communities that could no longer use law from a "fallen" empire to uphold church hierarchy.[254] Instead, the church adopted a feudalistic oath of loyalty, which became a condition of consecration which affected the hierarchy of church relations at every level.[120]

The church developed an oath of loyalty between men and their king to create a new model of consecrated kingship.[255] Janet Nelson writes that:

This rite has a continuous history in both Anglo-Saxon England and Francia from the eighth-century onward, with further refinements in the ninth and tenth. It is, among other things, a remarkable application of law by early medieval churchmen in the West, to which the East offers no parallel.[255]

Canon laws were created by councils, kings, and bishops, and by lay assemblies. Law was not state-sponsored, systematized, professionalized, or university-taught in this period.[253]

Monasticism

[edit]In 600, there was great diversity in monastic life, in both East and West, even though the basic characteristics of monastic spirituality - asceticism, the goal of spiritual perfection, a life of wandering or physical toil, radical poverty, preaching, and prayer - had become established.[212][note 6] Monasteries became more and more organized from 600 to 1100.[259] The formation of these organized bodies of believers gradually carved out social spaces with authority separate from political and familial authority, thereby revolutionizing social history.[260][note 7] Medical practice was highly important, and medieval monasteries are best known for their contributions to medical care.[273] For the majority of the faithful in the early Middle Ages of both East and West, the saint was first and foremost the monk.[274]

Art

[edit]

Dedicated monks merged the Germanic practice of painting small objects and the classical tradition of fine metalwork to create "illuminated" psalters, collections of the Psalms, the gospels, and copies of the Bible. First using geometric designs, foliage, mythical animals, and biblical characters, the illustrations became more realistic in the Carolingian Renaissance.[275]

In the 720s, the Byzantine Emperor Leo banned the pictorial representation of Christ, saints, and biblical scenes, destroying much of early art history. The West condemned Leo's iconoclasm.[276] By the tenth and early eleventh centuries, Byzantine culture began to recover.[277][278]

Papal supremacy

[edit]

Popes led the sixth-century response to the invasion of northern Italy by the Lombards (569) producing an increase in papal autonomy and prestige.[279] By the time Pope Gregory I succeeded to the papacy in 590, the claim of Rome's supremacy over the rest of the church - as stemming from Peter himself - was well established.[280] Gregory held that papal supremacy concerned doctrine and discipline within the church, but large sections of both the Western and Eastern churches remained unconvinced they should be submissive to the Roman See.[281][282]

In the century or so after Gregory the Great, the Pope's ability to lay down the law remained limited.[120] Papal supremacy did not yet translate to legal authority.[120] From the ninth to the eleventh-century, the Pope gave little general direction to the church exercising power locally in the manner of an aristocrat.[283][284][285]

Papal power rose as internecine competition increasingly led people to Rome to resolve disagreements.[120][286] The growing presence and involvement of the aristocracy in the papal bureaucracy, an increase in papal land-holdings from the second half of the sixth into the seventh-century, combined with changes in their administration that brought an increase in wealth, gradually shifted popes from being beneficiaries of patronage to becoming patrons themselves.[287] William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, and other powerful lay founders of monasteries, placed their institutions under the protection of the papacy in the tenth-century thereby facilitating another rise in papal power.[288][289][282]

High Middle Ages (842–1299)

[edit]Historical background of the High Middle Ages

[edit]In the second half of the eleventh century, three powerful groups – Seljuk Turks from the east, Almoravids from West Africa, and Crusaders from Europe – changed the politics, culture, and religious configurations of Byzantium and the European West.[290][note 8] Byzantium was weakened from repeated invasion, and its territorial frontiers had become nebulous, but economically and spiritually the core of the Byzantine Empire had never been more prosperous.[297][278] Conquest established a European economic foothold in the Middle East, and Europe became more connected to the world beyond it through commerce.[290] Ecclesiastical reform emerged in Europe, and influential new art and architecture were formed.[290]

The medieval papacy of this era gained authority in every domain of life.[298] Bishops were given the task of protecting the faith, dealing with infringements of church law, refining the definition of heresy, and punishing those deemed to be heretics.[299] The village parish emerged as one of the fundamental institutions of medieval Europe.[300][301][302]

This era includes tremendous religious devotion and reform, technological advancement, the intellectual revolution of High Scholasticism, and the Renaissance of the twelfth-century.[303][241][304]

Christendom 842-1099

[edit]Tenth and eleventh century reform

[edit]

Under Hugh of Cluny (1049–1109), the Abbey of Cluny became the leading centre of reform in Western monasticism from the eleventh into the early twelfth-century. The Cistercian movement, a second wave of reform after 1098, also became a primary force of technological advancement and its spread in medieval Europe. Technological advancements contributed to economic growth.[305][306][307]

Dissatisfaction with the way the archbishop ruled their city led the Milan commune, a collective movement for self-government, to win independence in 1097 demonstrating the importance of Church reform to the people.[308]

In Italy, Gregorian Reform (1050–1080) reached into the church and outward into society setting new standards for marriage, celibacy for priests, and divorce.[309][310] Beginning in the twelfth-century, Mendicant orders (Franciscans and Dominicans) embraced a significant and impactful change in understanding a monk's calling as a charge to actively reform the world.[311][312]

Investiture controversy (1078)

[edit]

The church appointed its bishops and abbots, but it was the nobles who owned the land, and they were the ones who had control over who got "invested" into a paying job on their land.[178][251][283] Under Gregory VII, the Roman Catholic Church was determined to end this duality. This produced the Investiture controversy which began in the Holy Roman Empire in 1078.[313] Specifically, the dispute was between the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, and Pope Gregory VII, over who had the right to invest a bishop or abbot, but more generally, it was over control of the church and its revenues.[314][315][316][317][note 9]

In this controversy, papal supremacy took a political turn. Gregory recorded a series of statements asserting that the church must be the higher of the two powers of church and state and that the church must no longer be treated as a servant to the state.[289][319][320] Disobedience to the Pope became equated with heresy.[321]

The Dictatus Papae of 1075 declared the pope alone could invest bishops.[313] Henry IV rejected the decree. This led to his excommunication, which contributed to a ducal revolt, that led to a civil war: the Great Saxon Revolt. Eventually, Henry received absolution. The conflict of investiture lasted five decades with a disputed outcome.[322][323][324] A similar controversy occurred in England.[325]

Toledo 1085

[edit]King Alfonso VI of León and Castile captured Toledo in 1085. It was a major victory in the Christian overthrow of Islam in Spain, but the Almoravids prevented it from going further at that time.[326]

First crusade (1095)

[edit]

In 1081, Alexios I Komnenos began to reform the Byzantine government. After a decade of addressing internal issues, he turned to Pope Urban and asked for help with the biggest external problem the Byzantines had: the Seljuk Turks.[327] Urban responded (1095) with an appeal to European Christians to "go to the aid of their brethren in the Holy Land".[328][329][330]

Urban's message had tremendous popular appeal, and there was much enthusiasm supporting it. It was new and novel and tapped into powerful aspects of folk religion. Voluntary poverty and its renunciation of self-will, along with a longing for the genuine "apostolic life," flourished in the late eleventh and twelfth centuries connecting pilgrimage, charity, remission of sins, and a willingness to fight.[331][332][note 10]

Crusading involved the church in certain paradoxes: Gregorian reform was grounded in distancing spirituality from the secular and the political, while crusade made the church dependent upon financing from aristocrats and kings for the most political of all activities: war.[334]

Crusades led to the development of national identities in European nations, increased division with the East, and produced cultural change.[335] Hotly debated by historians, the single most important contribution of the Crusades to Christian history was, possibly, the invention of the indulgence.[292]

Law and order (1099 - 1299)

[edit]With Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085), the scope of canon law had been extended, and the church had become a more imposing institution, consolidating its territory, and establishing a bureaucracy.[336][337][338][note 11] Popes from 1159 to 1303 were predominantly lawyers, not theologians.[341] New networks and new agencies were often manifested as legal services, and over it all watched an increasingly centralized and proactive church government.[338][342]

Throughout Christian Europe, church and civic rulers made efforts to support coherence and order.[343][297] Canon law became a large and highly complex system of laws that left out early Christian principles of inclusivity.[344][345][299] In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council met and accepted 70 canon laws.[346] The last three canons required Jews to distinguish themselves from Christians in their dress, prohibited them from holding public office, and prohibited Jewish converts from continuing to practice Jewish rituals.[347][note 12]

The papacy gradually came to resemble the monarchs of its day.[298] Still, it is the continuity of the papacy, the historical weight of its ongoing existence since at least Late Antiquity, that is the "hallmark of the [medieval] papacy" and a primary reason for its influence.[350]

Medieval Inquisition

[edit]Moral misbehavior and heresy, by the folk and clerics, were prosecuted by inquisitorial courts that were composed of both church and civil authorities.[351] The Medieval Inquisition includes the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230) and the Papal Inquisition (1230s–1240s), though these courts had no actual joint leadership or organization.[352][353][354] Created as needed, they were not permanent institutions but were limited to specific times and places.[355][356][357][note 13]

Medieval inquisitors did not possess absolute power, nor were they universally supported.[351] Riots and public opposition formed as inquisition became stridently contested both in and outside the Church.[355][360][361] The universities of Oxford and Prague produced some of the church's greatest inquisitorial experts as well as some of its most bitter foes.[362]

Learning

[edit]Traditionally, schools had been attached to monasteries. By the end of the eleventh century, Cathedral schools were established, and independent schools arose in some of the larger cities.[363] For most folk, learning began at home, then continued in the parish where they had been born and were associated with for the rest of their lives.[364] The clergy, and the laity, became "more literate, more worldly, and more self-assertive" and they did not always agree with the hierarchy.[302]

Scholasticism, Renaissance and science (1150-1200)

[edit]

Between 1150 and 1200, intrepid monks traveled to formerly Muslim locations in Sicily and Spain.[365] Fleeing Muslims had abandoned their libraries, and among the treasure trove of books, the searchers found the works of Aristotle, Euclid and more. Adapting Aristotelian logical reasoning and Christian faith created a revolution in thinking called scholasticism which elevated reason and reconciled it with faith.[366]

Scholasticism was a departure from the Augustinian thinking that had dominated the church for centuries. The writings of Thomas Aquinas are considered the height of scholastic thinking. His reconciliation of reason, law, politics, and faith provided the foundation for much modern thinking and law.[240][241][367][368]

Renaissance also included the revival of the scientific study of natural phenomena. Historians of science see this as the beginning of what led to modern science and the scientific revolution in the West.[369][370][371]

Universities

[edit]From the 1100s, Western universities, the first institutions of higher education since the sixth-century, were formed into self-governing corporations chartered by popes and kings.[372][373][374] Bologna, Oxford and Paris were among the earliest (c. 1150). Divided into faculties which specialized in law, medicine, theology or liberal arts, each held quodlibeta (free-for-all) theological debates amongst faculty and students and awarded degrees.[375][376] With this, both canon and civil law began to be professionalized.[338]

Art, architecture and music

[edit]

This was a period of enormous creativity characterised by an imposing public Christian art full of light, colour, and rhythm.[377] Romanesque style using Roman features with Christian influences, emerged in Europe between 1000 and 1200 as an aspect of the monastic revivals, especially the Cluniacs.[378] It was used primarily in architecture but also produced statuary, paintings, and illustrated manuscripts.[379]

Between 1137 and 1144 the Gothic style, with ribbed vaults and flying buttresses, such as those found in Notre Dames and the cathedral at Amiens, was invented.[380] The monk Guido of Arezzo modernized musical notation, invented the music staff of lines and spaces, and began the naming of musical notes making modern music possible.[381][382]

Spread and retraction of Christianity

[edit]Mesopotamia and Egypt

[edit]

By the end of the eleventh-century, Christianity was in full retreat in Mesopotamia and inner Iran. Some Christian communities further to the east continued to exist.[385][386]

The Christian churches in Egypt, Syria, and Iraq became subject to fervently Muslim militaristic regimes.[387] Christians were dhimma. This cultural status guaranteed Christian's rights of protection but discriminated against them through legal inferiority.[231] Various Christian communities adopted different strategies for preserving their identity while accommodating their rulers.[387] Some withdrew from interaction, others converted, while some sought outside help.[387]

Scandinavia

[edit]Christianization of Scandinavia (Sweden, Norway, and Denmark) occurred in two stages.[388] In the first stage, missionaries arrived on their own, without secular support, in the ninth-century.[389] Next, a secular ruler would take charge of Christianization in their territory. This stage ended once a defined and organized ecclesiastical network was established.[390] By 1350, Scandinavia was an integral part of Western Christendom.[391]

Russia

[edit]

From the 950s to the 980s, polytheism among the Kievan Rus declined, while many social and economic changes fostered the spread of the new religious ideology known as Christianity.[392] The event associated with the conversion of the Rus' has traditionally been the baptism of Vladimir of Kiev in 989.[393]

The new Christian religious structure was imposed by the state's rulers.[394] The Rus' dukes maintained control of the church which was financially dependent upon them.[395][note 14] While monasticism was the dominant form of piety, Christianity permeated daily life, for both peasants and elites, who identified themselves as Christian while keeping many pre-Christian practices.[397]

Baltic and central Europe

[edit]

Beginning under emperor Basil I (r. 867–886), Byzantine Christianity was instrumental in forming what would become Eastern Europe.[398][399] Serbia, Alania (modern Iran), Russia and Armenia were nascent Christian states by the early eleventh-century.[400][401][402] Romania,[403] Bulgaria,[404] Poland,[405] Hungary[406][407] and Croatia soon followed.[408]

Saints Cyril and Methodius translated the Bible, developing the first Slavic written script and the Cyrillic alphabet in the process. This became the educational foundation for all Slavic nations and influenced the spiritual, religious, literary, and cultural development of the entire region for generations.[392][409][410]

The East (1054)

[edit]The Seljuk Turks triumphed in Anatolia (1071) while the Turkic Pechenegs raided the Balkans (1087) and the Normans conquered Sicily (1093). The Byzantine army could not stop them. Emperors turned to diplomacy and the church.[411] Emperor Constantine IX (r.1042–1055) welcomed the Turkic Pechenegs in the Balkans by administering baptism, conferring titles, and settling them in depopulated regions. Emperors at times welcomed the Turks in the same process.[297]

The Byzantine East and the Catholic West had irreconcilable differences for centuries. Along with a general lack of charity and respect on both sides, there were also many cultural, geographical, geopolitical, and linguistic differences. In 1054, this produced the East–West Schism, also known as the "Great Schism", which separated the Church into Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[412][413][414]

Northern crusades (1147–1316)

[edit]

When the Second Crusade was called after Edessa fell, the nobles in Eastern Europe refused to go.[415] The Balts, the last major polytheistic population in Europe, had been raiding surrounding countries for several centuries, and subduing them was what mattered most to the Eastern-European nobles.[416] (These rulers saw crusade as a tool for territorial expansion, alliance building, and the empowerment of their own nascent church and state.[417]) In 1147, Eugenius' Divina dispensatione gave eastern nobility indulgences for the first of the Baltic wars (1147–1316).[415][418][419] The Northern Crusades followed intermittently, with and without papal support, from 1147 to 1316.[420][421][422] Priests and clerics developed a pragmatic acceptance of the forced conversions perpetrated by the nobles, despite the continued theological emphasis on voluntary conversion.[423]

Fourth Crusade (1204)

[edit]

In April of 1204, western crusaders in the Fourth Crusade stormed, captured, and looted Constantinople.[424][425][426] It was a severe blow.[427] Byzantine territories were divided among the Crusaders establishing the Latin Empire and the Latin takeover of the Eastern church.[428][429] By 1261, the Byzantines recaptured a much weakened and poorer Constantinople.[430][431]

Albigensian Crusade (1209 - 1229)

[edit]In 1209, Pope Innocent III and the King of France, Philip Augustus, began a military campaign to eliminate the Albigensian heresy known as Catharism.[432][433] Once begun, the campaign quickly took a political turn.[434] The king's army seized and occupied strategic lands of nobles who had not supported the heretics, but had been in the good graces of the Church. Throughout the campaign, Innocent vacillated, sometimes taking the side favouring crusade, then siding against it and calling for its end.[435] It did not end until 1229. The region was brought under the rule of the French king, thereby creating southern France, while Catharism continued for another hundred years (until 1350).[436][437]

Persecution of Jews

[edit]A turning point in Jewish-Christian relations took place in June 1239 when the Talmud was put "on trial", by Gregory IX (1237–1241) in a French court, over contents that mocked the central figures of Christianity.[438][439] This resulted in Talmudic Judaism being seen as so different from biblical Judaism that old Augustinian obligations to leave the Jews alone no longer applied.[440] As townfolk gained a measure of political power around 1300, they became one of Jewry's greatest enemies charging Jews with blood libel, deicide, ritual murder, poisoning wells and causing the plague, and various other crimes.[441][442] Although subordinate to religious, economic, and social themes, racial concepts also reinforced hostility.[443]

Jews had often acted as financial agents for the lords providing them loans with interest while being exempt from taxes and other financial laws themselves. This attracted jealousy and resentment.[444] Emicho of Leiningen massacred Jews in Germany in search of supplies, loot, and protection money. The York massacre of 1190 also appears to have had its origins in a conspiracy by local leaders to liquidate their debts along with their creditors.[445]

Late Middle Ages and early Renaissance (c. 1300–1520)

[edit]Historical setting

[edit]Attitudes and behaviours against the clergy identify the beginning of this period as a time of “anticlerical revolution".[446][note 15] The many calamities of the "long fourteenth-century" - plague, famine, multiple wars, social unrest, urban riots, peasant revolts, and renegade feudal armies – led folk to believe the end of the world was imminent.[448][449][450] This fear ran throughout society and became intertwined with anticlerical and anti-papal sentiments.[451][note 16]

Between 1300 and 1500, papal power stopped increasing, while kings continued to gain and consolidate power. A combination of events undermined the church's moral authority and constitutional legitimacy opening it to local fights of authority and control. Throughout this period, the church faced powerful challenges and vigorous political confrontations.[453][303][454][note 17]

Intolerance became one of the Late Middle Ages defining features.[460][461][462]

Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism (1309 - 1417)

[edit]![image of Portrait by Giuseppe Franchi of Pope John XXII (1316–1334) who was referred to as "the banker of Avignon".[463]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Portrait_of_Pope_John_XXII_Dueze_%28by_Giuseppe_Franchi%29_%E2%80%93_Pinacoteca_Ambrosiana.jpg/220px-Portrait_of_Pope_John_XXII_Dueze_%28by_Giuseppe_Franchi%29_%E2%80%93_Pinacoteca_Ambrosiana.jpg)

In 1309, Pope Clement V moved to Avignon in southern France in search of relief from Rome's factional politics. Seven popes resided there in the Avignon Papacy, but the move away from the "seat of Peter" caused great indignation and cost popes prestige and power.[464][465]

Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome in 1377.[466][467][449] After Gregory's death, the papal conclave met in 1378, in Rome, and elected an Italian Urban VI to succeed Gregory. The French cardinals did not approve, so they held a second conclave electing Robert of Geneva instead, giving the church two popes. This began the Western Schism.[468]

For the next thirty years the Church had two popes, then in 1409, the Pisan council called for the resignation of both popes, electing a third to replace them. Both Popes refused to resign, leaving the Church with three popes. Five years later, Sigismund the Holy Roman Emperor (1368-1437) pressed Pope John XXIII to call the Council of Constance (1414–1418) and depose all three popes. In 1417, the council elected Pope Martin V in their place.[469][470]

Criticism and reform (1300 - 1500)

[edit]Multiple strands of criticism of the clergy between 1100 and 1520 were voiced by clerics themselves. Such criticism condemned abuses and sought a more spiritual, less worldly, clergy.[471] However, there is a constancy of complaint in the historical record that indicates most attempts at reform between 1300 and 1500 failed.[472][473]

During the Late Middle Ages, groups of laymen and non-ordained secular clerics sought a more sincere spiritual life.[474] A vernacular religious culture for the laity arose.[332] The new devotion worked toward the ideal of a pious society of ordinary non-ordained people.[475] Inside and outside the church, women were central to these movements.[332]

Art and literature (c.1400 - 1600)

[edit]

During the European Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries, the Church was a leading patron of art and architecture, directly commissioning many individual works and supporting many artists such as Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bramante, Raphael, Fra Angelico, Donatello, and Leonardo da Vinci.[476][477]

Scholars revealed the Donation of Constantine as a forgery.[478]

Literature was deeply affected by Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus (1466 - 1536), an outstanding figure of Christian humanism which developed in the sixteenth century. Meant to further reform the church, humanists taught a simplified faith accessible by any Christian who could pray directly to God for themselves.[479]

The cult of chivalry evolved between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries and became a true cultural force that influenced art, literature, and philosophy.[480][481]

Byzantium and the Fall of Constantinople in 1453

[edit]In 1439, a reunion agreement between the Eastern and Western churches was made. However, there was popular resistance in the East, so it wasn't until 1452 that the decree of union was officially published in Constantinople. It was overthrown the very next year by the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.[482][483][note 18]

Compulsory resettlement returned many Greek Orthodox to Constantinople.[485] While Islamic law did not recognize the Patriarch as a "juristic person", nor acknowledge the Orthodox Church as an institution, it did identify the Orthodox Church with the Greek community, and concern for stability allowed it to exist.[486][487] The monastery at Mt. Athos prospered from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries.[488] Ottomans were largely tolerant, and wealthy Byzantines who entered monastic life there were allowed to keep some control over their property until 1568.[488]

Leaders of the church were recognized by the Islamic state as administrative agents charged with supervising its Christian subjects and collecting their taxes.[489] Compulsory taxes, higher and higher payments to the sultan in hopes of receiving his appointment to the Patriarchate, and other financial gifts, corrupted the process and impoverished Christians.[490][487] Conversion became an attractive solution.[491][note 19]

Modern Inquisition (1478 - twentieth century)

[edit]Between 1478 and 1542, the modern Roman, Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions were created with a much broader reach than previous inquisitions.[493][494][495]

The infamous Spanish Inquisition was responsible to the crown and was used to consolidate state interests.[496] Authorized by the Pope in 1478, it was begun in answer to Ferdinand and Isabella's fears that Jewish converts (known as Conversos or Marranos) were spying and conspiring with Muslims to sabotage the new state.[497][498] Of those condemned by the Inquisition of Valencia before 1530, ninety-two percent were Jews.[499]

Initially, the Spanish Inquisition was so severe that the Pope attempted to shut it down. King Ferdinand is said to have threatened the Pope to prevent that.[500][501][502] Five years after its inception, a papal bull conceded control of the Spanish Inquisition to the Spanish crown in October 1483.[503][502] It became the first national, unified, centralized institution of the nascent Spanish state.[504][496]

The Portuguese Inquisition was controlled by a state-level board of directors sponsored by the king who, during this period, was generally more concerned with ethnic ancestry than religion. According to Giuseppe Marcocci, there is a connection between the growth of the Inquisition and the statutes of blood purity.[494] Anti-Judaism became part of the Inquisition in Portugal before the end of the fifteenth-century, and forced conversion led many Jewish converts to Portuguese colonies in India where they suffered as targets of the Goa Inquisition.[505]

The Roman Inquisition operated to serve the papacy's long-standing political aims in Italy.[506] The Roman Inquisition was bureaucratic, intellectual, and academic.[507] It is probably best known for its condemnation of Galileo.[508]

Expulsion of Jews (circa 1200s - 1500s)

[edit]

While the medieval Catholic church never advocated the full expulsion of Jews from Christendom, nor did the Church ever repudiate Augustine's doctrine of Jewish witness, canon law supported discrimination. Secular rulers repeatedly evicted Jews from their lands and confiscated Jewish property.[509][510][511] In 1283, the Archbishop of Canterbury spearheaded a petition demanding restitution of usury and urging the Jewish expulsion in 1290.[512][513]

Frankfurt's Jews flourished between 1453 and 1613 despite harsh discrimination. They were restricted to one street and were subject to strict rules if they wished to leave this territory, but within their community, they were allowed to maintain some self-governance. They had their own laws, leaders, and a well-known Rabbinical school that also functioned as a religious and cultural centre.[510]

Early modernity (1500–1750)

[edit]Historical background

[edit]Powerful and pervasive ecclesiastical reform developed from medieval critiques of the church, but the institutional unity of the church was shattered.[514] Church critics of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries had challenged papal authority. Kings and councils asserting their own power had also created challenges to church authority, while vernacular gospels challenged church authority amongst the laity.[515][516]

Protestant Reformation

[edit]Though there was no actual schism until 1521, the Protestant Reformation (1517–1648) has been described (since the nineteenth-century) as beginning when Martin Luther, a Catholic monk advocating church reform, nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the church door in Wittenberg in 1517.[517]

Luther's theses challenged the church's selling of indulgences, the authority of the Pope, and various teachings of the late medieval Catholic church. This act of defiance and its social, moral, and theological criticisms brought Western Christianity to a new understanding of salvation, tradition, the individual, and personal experience in relationship with God.[518] Edicts handed down by the Diet of Worms condemned Luther and officially banned citizens of the Holy Roman Empire from defending or propagating his ideas.[519][520]

The three primary traditions to emerge directly from the Reformation were the Lutheran, Reformed, and the Anglican traditions.[521] At the same time, a collection of loosely related groups that included Anabaptists, Spiritualists, and Evangelical Rationalists, began the Radical Reformation in Germany and Switzerland.[522] Beginning in 1519, Huldrych Zwingli spread these teachings in Switzerland leading to the Swiss Reformation.[523]

Counter-Reformation

[edit]

The Roman Catholic Church rebuked the Protestant challenge in what is called the Counter-Reformation or Catholic Reformation, spearheaded by a series of 10 reforming popes from 1534 to 1605, beginning with Pope Paul III (1534–1549).[524] The Council of Trent (1545–1563) denied each Protestant claim, and laid the foundation of Roman Catholic policies up to the twenty-first-century.[525] A list of books detrimental to faith or morals was established, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, which included the writings of Protestants and those condemned as obscene.[526]

New monastic orders were formed within the church, including the Society of Jesus - also known as the "Jesuits" - who adopted military discipline and a vow of loyalty to the Pope, leading them to be called "the shock troops of the papacy". They soon became the Church's chief weapon against Protestantism.[525] Monastic reform also led to developments within orthodox spirituality, such as that of the Spanish mystics and the French school of spirituality.[527] The Counter-Reformation also created the Uniate church which used Eastern liturgy but recognized Rome.[528]

Internecine wars

[edit]The quarreling royal houses, already involved in dynastic disagreements, became polarized into the two religious camps as religion became entangled with local politics.[529] Warfare initially broke out in the Holy Roman Empire with the minor Knights' War in 1522, then intensified in the First Schmalkaldic War (1546–1547) and the Second Schmalkaldic War (1552–1555).[530][531] In 1562, France became the centre of religious warfare.[532] The largest and most disastrous of these wars was the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which severely strained the continent's political system.[533]

Theorists such as John Kelsay and James Turner Johnson argue that these wars were varieties of the just war tradition for liberty and freedom.[534] William T. Cavanaugh identifies a view shared by many historians that the wars were not primarily religious, but were more about state-building, nationalism, and economics.[535][536][532] Historian Barbara Diefendorf argues that religious motives were always mixed with other motives, but the simple fact of Catholics fighting Catholics and Protestants fighting Protestants is not sufficient to prove the absence of religious motives.[537] According to Marxist theorist Henry Heller, there was "a rising tide of commoner hostility to noble oppression and growing perception of collusion between Protestant and Catholic nobles".[538]

Witch trials

[edit]Until the 1300s, the official position of the Roman Catholic Church was that witches did not exist.[539] While historians have been unable to pinpoint a single cause of what became known as the "witch frenzy", scholars have noted that, without changing church doctrine, a new but common stream of thought developed at every level of society that witches were both real and malevolent.[540] Records show the belief in magic had remained so widespread among the rural people, that it has convinced some historians that Christianization had not been as successful as previously supposed.[541] The main pressure to prosecute witches came from the common people, and trials were mostly civil trials.[542][543] There is broad agreement that approximately 100,000 people were prosecuted, of which 80% were women, and that 40,000 to 50,000 people were executed between 1561 and 1670.[544][540]

Modern concepts of tolerance

[edit]Since the 1400s, Protestants steadfastly sought religious toleration for heresy, blasphemy, Catholicism, non-Christian religions, and even atheism.[545] Anglicans and other Christian moderates also wrote and argued for toleration.[546] In the 1690s, many secular thinkers were rethinking on a political level all of the State's reasons for persecution, and they also began advocating for religious toleration.[547][548] Over the next two and a half centuries, many treaties and political declarations of tolerance followed, until concepts of freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and freedom of thought became established in most western countries.[549][550][551]

Eastern-Orthodox Churches

[edit]The conquest of 1453 had effectively destroyed the Eastern Orthodox Church as an institution of the Christian empire as inaugurated by Constantine, sealing off Greek-speaking Orthodoxy from the West for almost a century and a half.[552][553] However, the Seljuq sultans and the Ottoman sultans were relatively tolerant, recognizing Christians as fellow "people of the book". Still, the church was without one of its leaders, the Emperor, though it retained a patriarch in a lesser and more limited capacity.[554] This allowed the spiritual and cultural influence of the Eastern church, Constantinople, and Mount Athos the monastic peninsula to continue in slightly altered form among Orthodox nations.[553] By the time of Süleyman the Magnificent (1520 – 1566), the patriarchate had become a part of the Ottoman system, and continued to influence the Orthodox world.[492][487] Throughout all of this, Constantinople remained conservative and suspicious of Rome.[555]

Elizabeth Zachariadou writes that "The personality of Jeremias II dominates the history of the patriarchate during the second half of the sixteenth century".[555] Jeremias (1536 - 1595) established contact with the new Protestant Lutherans. Nothing much resulted beyond Western Europeans becoming more aware of the problems of the church in captivity.[555] Jeremias was the first Eastern patriarch to visit north-eastern Europe. Ending his visit in Moscow, he founded the Orthodox Patriarchate of Russia.[555][487]

A generation after Constantinople fell to the Turks Ivan III of Muscovy adopted the style of the ancient Byzantine imperial court. This gained Ivan support among the late fifteenth and early sixteenth-century Rus elite who saw themselves as the New Israel and Moscow as the new Jerusalem.[556] The Church reform of Peter I in the early eighteenth-century placed the Orthodox authorities under the control of the tsar. An ober-procurator appointed by the tsar ran the committee that governed the Church after 1721 until 1918: the Most Holy Synod. The Church became involved in the various campaigns of russification and contributed to antisemitism.[557][558]

The Age of Enlightenment (17th-18th c.)

[edit]The era of absolutist states followed the breakdown of Christian universalism.[559] Abuses from political absolutism practiced by kings supported by Catholicism, gave rise to a virulent anti-clerical, anti-Catholic, and anti-Christian sentiment that emerged in the 1680s.[560] Critique of Christianity began among the more extreme Protestant reformers enraged by fear, tyranny, and persecution.[561][562] Secularisation spread as every level of European society began to embrace enlightenment ideals.[563]

Art

[edit]In the early seventeenth-century, Baroque art, characterized by grandeur and opulence, offered the Catholic Church and secular rulers a means of expressing their magnificence and political power.[564] This was a period of turmoil, discovery, and change, and Baroque art reflected the search for stability and order.[565] It originated in Rome and became an international style. The church of St.Peter in Rome, St. Paul's cathedral in London, and the gardens at Versailles are probably the age's premiere examples.[566]

Colonialism and missions

[edit]Colonialism opened the door for Christian missions in many new regions.[567][568][569] According to Sheridan Gilley "Catholic Christianity became a global religion through the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires in the sixteenth-century and French missionaries in the seventeenth and eighteenth."[568]

However, Christian missionaries and colonial empires had separate agendas, and they were often in direct opposition to each other.[570]

Most missionaries avoided politics, yet they also generally identified themselves with the indigenous people amongst whom they worked and lived.[571] On the one hand, vocal missionaries challenged colonial oppression and defended human rights, even opposing their own governments in matters of social justice for 500 years.[571] On the other hand, there are an equal number of examples of missionaries cooperating with colonial governments.[572]

Asia

[edit]The sixteenth-century success of Christianity in Japan was followed by one of the greatest persecutions in Christian history. Sixteenth-century missions to China were undertaken primarily by the Jesuits.[232][573] Sheridan Gilley writes that "The cruel martyrdom of Catholics in China, Indochina, Japan and Korea, another heroic missionary country, was connected to local fears of European invasion and conquest, which in some cases were not unjustified."[574]

Late modernity (1750–1945)

[edit]Historical setting

[edit]Historians often refer to the period from 1760 to 1830 as a "historical watershed" because it embraces the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution all of which produced long-term changes.[575] The American Revolution (1776) and its aftermath included legal assurances of the separation of church and state and a general turn to religious plurality.[576][577][578] In the decades following, France also experienced revolution, and by 1794, radical revolutionaries attempted to violently ‘de-Christianize’ France in what some scholars have termed a "deliberate genocidal policy of extermination" of Catholics in the Vendée region.[579] When Napoleon came to power, he acknowledged Catholicism as the majority view and tried to make it dependent upon the state.[580] For Eastern Orthodox church leaders, the French Revolution meant Enlightenment ideas were too dangerous to embrace.[487]

Scholars have identified a positive correlation between the rise of Protestantism and human capital formation,[581] the Protestant work ethic,[582] economic development,[583] and the development of the state system.[584] Max Weber says Protestantism contributed to the development of banking across Northern Europe and gave birth to Capitalism.[585][note 20] However, the urbanization and industrialization that went hand in hand with capitalism created a plethora of new social problems.[587][588] In Europe and North America, both Protestants and Catholics provided massive aid to the poor, supporting family welfare, medicine, and education.[589]

In many cases, throughout this period, Christianity was weakened by social and political change.[588] By the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries, the influence of anticlerical socialism and communism produced secession and disruption in many locations.[590]

Biblical criticism, liberalism, fundamentalism

[edit]After the Scientific Revolution (1600–1750), an upsurge in skepticism subjected Western culture, including religious belief, to systematic doubt.[591] Biblical criticism emerged (c. 1650 – c. 1800), pioneered by Protestants, using historicism and human reason to make the study of the Bible more scholarly, secular, and democratic.[592][593][594] Depending upon how radical the individual scholar was, this produced different and often conflicting views, but it posed particular problems for the literal Bible interpretation which had emerged in the 1820s.[595][596][597]

Before the Enlightenment of the eighteenth-century, liberalism was synonymous with Christian Idealism in that it imagined a liberal State that embraced political and cultural tolerance and freedom.[596] Later liberalism embraced seventeenth-century rationalism, which was attempting to "wean" Christianity from its "irrational cultic" roots.[598] This liberalism lost touch with the necessity of faith and ritual in maintaining Christianity which led to liberalism's decline and the birth of fundamentalism.[599]

Fundamentalist Christianity arose in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century as a reaction against modern rationalism.[597] The Roman Catholic Church became increasingly centralized, conservative, and focused on loyalty to the Pope.[594] Early in the twentieth-century, the Pope required Catholic Bible scholars who used biblical criticism to take an anti-modernist oath.[594][600]

In the same period (1925), supporters of a relatively new, loosely organized, and undisciplined Protestant fundamentalism participated in the Scopes trial. By 1930, the movement appeared to be dying.[601][602] Later in the 1930s, Neo-orthodoxy, a theology against liberalism with a reevaluation of Reformation teachings, began uniting moderates of both sides.[603] In the 1940s, "new-evangelicalism" established itself as separate from fundamentalism.[604]