Saint Barbara

Barbara | |

|---|---|

St. Barbara with her attribute – three-windowed tower, central panel of St. Barbara Altarpiece (1447), National Museum in Warsaw | |

| Virgin and martyr | |

| Born | Mid-third century Heliopolis (Roman Phoenicia) or Nicomedia, Bithynia |

| Died | Late-third century to early-fourth century (executed by her father) |

| Venerated in | |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Three-windowed tower, palm, chalice, lightning, a crown of martyrdom |

| Patronage | Paternò, Rieti (Italy); armourers; architects; artillerymen; firemen; firework makers; mathematicians; miners; tunnelers; lightning; chemical engineers; prisoners; Lebanon; Royal Air Force Armourers |

Saint Barbara (Ancient Greek: Ἁγία Βαρβάρα; Coptic: Ϯⲁⲅⲓⲁ Ⲃⲁⲣⲃⲁⲣⲁ; Church Slavonic: Великомученица Варва́ра Илиопольская; Arabic: القديسة الشهيدة بربارة), known in the Eastern Orthodox Church as the Great Martyr Barbara, was an early Christian Greek saint and martyr. There is no reference to her in the authentic early Christian writings nor in the original recension of Saint Jerome's martyrology.[1]

Saint Barbara is often portrayed with miniature chains and a tower to symbolize her father imprisoning her. As one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, Barbara is a popular saint, perhaps best known as the patron saint of armourers, artillerymen, military engineers, miners and others who work with explosives because of her legend's association with lightning.

She is also the patron saint of mathematicians. A 15th-century French version of her story credits her with thirteen miracles, many of which reflect the security she offered that her devotees would not die before getting to make confession and receiving extreme unction.[2]

Despite the legends detailing her story, the earliest references to her supposed 3rd-century life do not appear until the 7th century, and veneration of her was common, especially in the East, from the 9th century.[2] Because of doubts about the historicity of her legend,[3][4] she was removed from the General Roman Calendar in the 1969 revision, though not from the Catholic Church's list of saints.[5]

Life

[edit]

According to the hagiographies,[2][6] Barbara was born either in Heliopolis or in Nicomedia,[7] the daughter of a rich pagan named Dioscorus who carefully guarded her, keeping her locked up in a tower to preserve her from the outside world. After she secretly became a Christian, she rejected an offer of marriage that she received through her father.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13] There is no reference to her in the authentic early Christian writings nor in the original recension of Saint Jerome's martyrology.[1]

Before departing on a journey, Barbara's father commanded that a private bath-house be erected for her use near her dwelling, and during his absence, she had three windows put in it as a symbol of the Holy Trinity, instead of the two originally intended. When her father returned, she acknowledged herself to be a Christian. Dragged before the prefect of the province, Martinianus, who had her cruelly tortured, Barbara held true to her Christian faith. During the night, the dark prison was bathed in light and new miracles occurred. Every morning, her wounds were healed. Torches that were to be used to burn her went out as soon as they came near her. Finally, she was condemned to death by beheading. Her father himself carried out the death sentence; however, as punishment, he was struck by lightning on the way home and his body was consumed by flame. Barbara was buried by a Christian, Valentinus, and her tomb became the site of miracles. This summary omits picturesque details, supplemented from Old French accounts.[2]

According to the Golden Legend, her martyrdom took place on 4 December "in the reign of emperor Maximianus and Prefect Marcien" (r. 286–305); the year was given as 267 in the French version edited by Father Harry F. Williams of the Anglican Community of the Resurrection (1975).

Veneration

[edit]

The name of Saint Barbara was known in Rome in the 7th century;[2] her cult can be traced to the 9th century, at first in the East. Since there is no mention of her in the earlier martyrologies, her historicity is considered doubtful.[14]

Her legend is included in Vincent of Beauvais' Speculum historiale (xii.64) and in later versions of the Golden Legend[15] (and in William Caxton's version of it).

Various versions, which include two surviving mystery plays, differ on the location of her martyrdom, which is variously given as Tuscany, Rome, Antioch, Baalbek, and Nicomedia.[16]

Saint Barbara is one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. Her association with the lightning that killed her father has caused her to be invoked against lightning and fire; by association with explosions, she is also the patron of artillery and mining.[17]

Her feast, 4 December, was introduced in Rome in the 12th century and included in the Tridentine calendar. In 1729, that date was assigned to the celebration of Saint Peter Chrysologus, reducing that of Saint Barbara to a commemoration in his Mass.[6]: 98 In 1969, it was removed from that calendar, because the accounts of her life and martyrdom were judged to be entirely fabulous, lacking clarity even about the place of her martyrdom.[6]: 147 However, she is still mentioned in the Roman Martyrology,[18] which, in addition, lists another ten martyr saints named Barbara.

In the 12th century, the relics of Saint Barbara were brought from Constantinople to the St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery in Kyiv, where they were kept until the 1930s, when they were transferred to St. Volodymyr's Cathedral in the same city. In November 2012, Patriarch Filaret of The Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kiev Patriarchate transferred a small part of St. Barbara's relics to St. Andrew Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral in Bloomingdale, Illinois.

Her feast day for Roman Catholics[5] and most Anglicans is 4 December.

In 2022, Barbara was officially added to the Episcopal Church liturgical calendar with a feast day she shares with Catherine of Alexandria, and Margaret of Antioch on 24 November.[19]

Patronage

[edit]

Saint Barbara is venerated by Catholics who face the danger of sudden and violent death at work. She is invoked against thunder and lightning and all accidents arising from explosions of gunpowder.[20][21] She became the patron saint of artillerymen, armourers, military engineers, gunsmiths, and anyone else who worked with cannon and explosives.[22][23] Following the widespread adoption of gunpowder in mining in the 1600s, she was adopted as the patron of miners, tunnellers,[17] and other underground workers. As the geology and mine engineering developed in association with mining, she became patron of these professions.

The Spanish word santabárbara, the corresponding Italian word santabarbara, and the obsolete French Sainte-Barbe, signify the powder magazine of a ship or fortress.[24] It was customary to have a statue of Saint Barbara at the magazine to protect the ship or fortress from suddenly exploding.[24] Saint Barbara is the patron of the Italian Navy.[20][23]

Within the tunneling industry, as a long-standing tradition, one of the first tasks for each new tunnelling project is to establish a small shrine to Santa Barbara at the tunnel portal or at the underground junction into long tunnel headings. This is often followed with a dedication and an invocation to Santa Barbara for protection of all who work on the project during the construction period.[25][26]

In English-speaking countries

[edit]The church at HMS Excellent (also known as Whale Island) Portsmouth, Hampshire, England, the former Gunnery School of the Royal Navy, is called St. Barbara's.

Saint Barbara was also the Patron saint of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps of the British Army, a church being dedicated to her, initially at Hilsea Barracks Portsmouth, and later being moved to Backdown in Surrey, when the Corps moved its training establishment there. Saint Barbara's Day, 4 December, is celebrated by the British (Royal Artillery, RAF Armourers, Royal Engineers), Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Armourers, Australian (Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery, RAAF Armourers), Canadian (Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technicians (EOD), Canadian Ammunition Technicians, Canadian Air Force Armourers, Royal Canadian Artillery, Canadian Military Field Engineers, Royal Canadian Navy Weapons Engineering Technicians), and New Zealand (RNZN Gunners Branch, RNZA, Royal New Zealand Army Ordnance Corps, RNZAF Armourers) armed forces.[citation needed]

The Irish Army venerates her as the patron saint of the Artillery Corps where she appears on the corps insignia, half dressed, holding a harp, sitting on a field cannon.

Saint Barbara is recognized as the patron saint of the field artillerymen of the Marine Corps 1st Marine Division, who commemorate Saint Barbara's Day with a dinner and the traditional preparation artillery punch.[27] Saint Barbara is the patron saint of the United States Field Artillery Association. To recognize the vital roles spouses and families play in the lives of field artillery soldiers and marines, the units celebrate Saint Barbara's Day with military balls or dinners and other activities.[28] Although they do not celebrate her saint's day, she is also the patron saint of US Navy and Marine Corps Aviation Ordnancemen.[citation needed] It is celebrated by the Norwich University Artillery Battery with a nighttime fire mission featuring multiple M116 howitzers.[citation needed]

Several mining institutions also celebrate it, such as some branches of the Australian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy.[citation needed] The West Australian Mining Club celebrate Saint Barbara's Day and use it to remember those people who have died working in the mining industry during the year.[citation needed]

In the mining town Kalgoorlie, Australia, as patron saint of miners she is venerated in the annual St. Barbara's Day parade.[29][30] In New Zealand the Moawhango Tunnel on the Tongariro Power Scheme was built by Italian tunnellers and commissioned on 4 December 1979.[31][32]

Central Europe

[edit]

In Germany, Barbarazweig is the custom of bringing branches into the house on December 4 to bloom on Christmas.[33] Saint Barbara is revered as a patron saint of miners and in extension, the geosciences in general, including the tunneling industry.[34][35] This connection is particularly strong in the Catholic areas of Germany, as for example Bavaria. Some university geology departments hold annual 'Barabarafests' if not on the 4th then the closest Friday,[36] or within Baden-Württemberg, see University of Tübingen,[37] University of Freiburg[38] or University of Bonn[39] or applied geosciences of the Technische Universität Darmstadt in Hesse.[40]

In the Czech Republic, a statue of Saint Barbara is placed near the future tunnel portal during the groundbreaking ceremony of most major tunneling projects, owing to her being the patron saint of miners.[41] In the town of Kutná Hora, a former silver mining center, the cathedral is dedicated to Saint Barbara.[42]

In Poland, the salt mine at Wieliczka honours Saint Barbara in Saint Kinga's chapel.[43]

In France, due to the historic link between the firefighters and the military sappers, Saint Barbara is also the patron of firefighters and has thus been celebrated by fire services throughout the country on December 4 since the Third Republic.[44]

Spain, Portugal and former colonies

[edit]The Spanish military artillerymen, mining engineers and miners also venerate her as patron saint. Parades, masses, dinners and other activities are held in her honour.[citation needed]

A portion of the coast of California, now occupied by the city of Santa Barbara, California and located approximately 100 miles northwest of Los Angeles, is named after her.[45] The City of Santa Barbara got its name from the early Spanish navigator Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo. On December 4, the explorer stopped at a particular place on the California coast. He chose to name the spot after the patron of that day, Saint Barbara.[46] A Roman Catholic missionary church, the Mission Santa Barbara, was founded there on her feast day in 1786, and is one of the twenty-one such churches that were operated by the Franciscan Order and collectively known as the California missions. The Presidio of Santa Barbara was built in 1782, with the mission of defending the Second Military District in Spanish California. Santa Barbara County was one of the twenty-seven original counties of California, formed in 1850 at the time of statehood.[47] The county's territory was later divided to create Ventura County in 1873.[48]

Other Spanish and Portuguese settlements named Santa Barbara were established in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, Venezuela, and the Philippines.[49]

In the Afro-Cuban religion of Santería, Barbara is syncretized with Chango, the deity of fire, lightning, and thunder.[50]

Eastern Europe, Eastern Orthodox Church

[edit]In Ukraine, alleged[51] relics of Saint Barbara are kept in St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery.[52][53][54] A church of the Great Martyr Barbara (Храм великомучениці Варвари) of Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) is located near Kyrylivskyi Hai (Кирилівський Гай) park in Kyiv. In 2019 the 19th Missile Brigade of the Ukrainian Ground Forces received the honorary title "Saint Barbara".[55]

In Georgia, Saint Barbara's Day is celebrated as Barbaroba on December 17 (which is December 4 in the old style calendar).[56] The traditional festive food is lobiani, bread baked with a bean stuffing.

In Greece and Cyprus, the day is celebrated by the Artillery Corps of the Greek Army and the Cypriot National Guard. Artillery camps throughout the two countries host celebrations in honor of the saint, where loukoumades, a traditional sweet, are offered to soldiers and visitors, supposedly because they resemble cannonballs.[57] Saint Barbara is also the patron saint of the northern Greek city of Drama, where a sweet called varvara, which resembles a more liquid form of koliva, is prepared and consumed on her feast day.[citation needed]

In North Macedonia Saint Barbara's day is celebrated by the Eastern Orthodox, as Варвара (Varvara) on 17 December. Some Macedonians celebrate with their closest family and friends at home, while others refrain, believing that people who step in their house on Saint Barbara's day will give them either good or bad luck for the rest of the year.[citation needed]

In Armenia, a cave shrine to Saint Barbara (Kuys Varvara) is located on the slopes of Mount Ara and lit candles and flower garlands are used as tribute.[citation needed]

Many churches in Russia are dedicated in her name, including one in Moscow, next to Saint Basil's Cathedral, and in Yaroslavl.[58]

The Order of Saint Barbara

[edit]

The United States Army Field Artillery Association and the United States Army Air Defense Artillery Association maintain the Order of Saint Barbara as an honorary military society of the United States Army Field Artillery and the United States Army Air Defense Artillery. Members of both the United States Army and United States Marine Corps, along with their military and civilian supporters, are eligible for membership.[28]

Saint Barbara's Day

[edit]In many mining communities, families follow the custom of the "Barbara branch". On December 4 cherry tree sprigs are cut and placed in a vase filled with water close to the light. After about 21 days, these branches blossom. In the Westerwald, the Barbara sprigs were regarded as a symbol of Christmas.[59]

Italy

[edit]The feast of Santa Barbara is the main religious feast of Paternò, in the province of Catania, dedicated to Santa Barbara, the patron saint of the city, originally from Nicomedia, in Bithynia (current İzmit in Turkey) and martyred according to tradition in 306 by father Dioscuro.

The event takes place annually on 3, 4, 5 and 11 December, 27 May and 27 July. 4 December represents the date of the martyrdom of the saint, 27 May is the feast of the patronage of Santa Barbara during which the miracle of the stopping of the eruption of Etna in 1780 is remembered, while 27 July is the feast of the arrival of the relics that were brought to Paternò in 1576.[60][61]

Eid il-Burbara

[edit]

The Feast of Saint Barbara, is celebrated amongst Middle Eastern Christians in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, and Turkey (Hatay Province).[62]

Eid il-Burbara or Saint Barbara's day is celebrated in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, and Hatay Province among Arab Christians annually on December 4, in a feast day similar to that of North American Halloween.[63][64] The traditional food for the occasion is Burbara, a bowl of boiled wheat, barley, pomegranate seeds, raisins, anise and sugar. Shredded Coconut, Walnuts or almonds can be added.[65][66] The general belief among Lebanese Christians is that Saint Barbara disguised herself in numerous characters to elude the Romans who were persecuting her, and the tradition states that when the saint was escaping from the army of the pagan king in Baalbek, she passed in a field of wheat, and the wheat grew miraculously in order to hide her footprints from the soldiers, and this is the reason of serving the traditional wheat dessert on the feast day. In the Christian village of Aboud in the West Bank, there is a shrine in a cave that the saint reportedly took refuge in.[67] It may also be celebrated on December 17.

Cultural legacy

[edit]

The name of the barbiturate family of pharmaceutical drugs is believed to derive from the suggestion by an artilleryman commemorating the feast of Saint Barbara in 1864, whom the chemist Adolf von Baeyer encountered at a local tavern whilst celebrating his recent discovery of the parent compound.[68]

St. Faustina wrote that St. Barbara appeared to her on 22 August 1937. "This morning, Saint Barbara, Virgin, visited me and recommended that I offer Holy Communion for 9 days on behalf of my country and thus appease God's anger. This virgin was wearing a crown made of stars and was holding a sword in her hand...With her white dress and her flowing hair, she was so beautiful that if I had not already known the Virgin Mary I would have thought that it was she. Now I understand that each virgin has a special beauty all her own; a distinct beauty radiates from each of them."[69]

Saint Barbara is mentioned in Thomas Pynchon's novel Against the Day. The December fourth holiday is compared to the Fourth of July, as being more celebrated by the Dynamiters.[citation needed] She is also mentioned in Federico García Lorca's play La Casa de Bernarda Alba (1936). According to this drama, a popular Spanish phrase regarding this saint in the early 20th century was:"Blessed Santa Barbara, your story is written in the sky, with paper and holy water."

The first Spanish-language telenovela filmed in colour for TV in the US was the 1973 production of Santa Bárbara, Virgen y Mártir, filmed entirely on location in Hialeah, Florida.[citation needed]

G. K. Chesterton wrote the Ballad of Saint Barbara,[70] interweaving the Legend of the Saint with the contemporary account of the huge artillery barrages that turned the First Battle of the Marne.

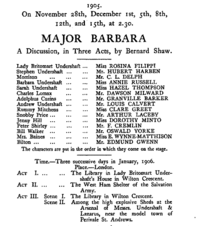

Major Barbara is a play by George Bernard Shaw in which the title character, an officer in the Salvation Army, grapples with the moral dilemma of whether this Christian denomination should accept donations from her father, who is an armaments manufacturer.[71]

In "Time Bomb", an episode of The Closer, the LAPD deploy a bomb-squad robot named Babs, after St. Barbara in her role as patron saint of artillery and explosives personnel.[citation needed]

Saint Barbara's story is mentioned in a live version of The Hold Steady's song "Don't Let Me Explode" from Lollapalooza.

The original play "Hala and the King" هالة والملك (مسرحية) of the Rahbani brothers starring Fairuz is based on the traditional celebrations of the Saint Barbara Feast in Lebanon, the songs of the first act use the same musical rhyme used by the children until today during the feast, and the concept of costumes in the play is based on the local practices during the feast.

Sylvia Rivera, the co-founder of the homelessness relief organization Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, would lead prayers to Saint Barbara among members of STAR and felt a strong connection to the saint.[72][73]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kirsch, Johann Peter. "St. Barbara." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907

- ^ a b c d e Harry F. Williams, "Old French Lives of Saint Barbara" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 119.2 (16 April 1975:156–185), with extensive bibliography.

- ^ Medieval historian Norman F. Cantor referred to Barbara in passing as "entirely mythical', in In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made 2002:84

- ^ Kirsch, Johann Peter "St. Barbara." The Catholic Encyclopedia] Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907

- ^ a b Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2001 ISBN 978-88-209-7210-3), p. 621

- ^ a b c Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice 1969)

- ^ a b Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, Oxford University Press, G. Ferguson, 1959, p. 107.

- ^ Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses, D. Gifford, Robert J. Seidman, University of California Press, 2008, ISBN 0520253973, p. 527.

- ^ A Cultural Encyclopedia of Lost Cities and Civilizations, ABC-CLIO, Michael Shally-Jensen, Anthony Vivian, 2022, p. 55.

- ^ The Descent of the Soul and the Archaic Katábasis and Depth Psychology, Leslie Gardner, Paul Bishop, Terence Dawson, Taylor & Francis, 2022, ISBN 9781000656619, p. 136.

- ^ Livingstone, E. A. LivingstoneE A. (2006), Livingstone, E. A. (ed.), "Barbara, St", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198614425.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-861442-5, retrieved 2024-09-07

- ^ Robuschi, Luigi (2022-09-01). "SECULAR HEROINES AND CHRISTIAN MARTYRS IN THE VENETIAN MEDITERRANEAN: ANNA ERIZZO AND ARNALDA OF ROCHAS. | Nuova Rivista Storica | EBSCOhost". openurl.ebsco.com. Retrieved 2024-09-07.

- ^ van Dijk, Mathilde (2021). "Epilogue: Beyond Binaries: A Reflection on the (Trans) Gender(s) of Saints". University of Cambridge: 271. doi:10.1017/9789048540266.012. ISBN 978-90-485-4026-6.

- ^ Alexander Joseph Denomy, "An old French life of Saint Barbara", Medieval Studies 1 (1939:148–78) publishes a 13th- or 14th-century poem in octasyllabic couplets; Wilhelm Weyh, Die syrische Barbara-Legende (Schweinfurt, 1912), concludes that the first legenda was in Greek.

- ^ B. de Gaiffier Analecta bollandiana77 (1959)5–41, suggests that the Legenda Aurea version was inspired by one from the late 15th-century Augustinian Jean de Wackerzeele, also known as Jean de Louvain (noted by Williams 1975:1758 note 17).

- ^ Bulfinch, (2001). One Hundred Saints. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Company.

- ^ a b Shaver, Katherine (2018-12-27). "As workers toil underground, Saint Barbara keeps watch". Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2001 ISBN 88-209-7210-7)

- ^ "General Convention Virtual Binder". www.vbinder.net. Archived from the original on 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2022-07-22.

- ^ a b "St. Barbara". Catholic Online. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Saint Barbara". Saint Barbara Parish. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ^ "Saint Barbara Nomination" (PDF). USFAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- ^ a b Kinard, Jeff (2007). Artillery : an illustrated history of its impact. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN 9781851095612.

- ^ a b Caprio, Betsy (1982). The Woman Sealed in the Tower—Being a View of Feminine Spirituality As Revealed by the Legend of Saint Barbara. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809124862.

- ^ "Santa Barbara watches over tunnellers". tunneltalk.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "London: Crossrail workers seek protection of Saint Barbara". Independent Catholic News. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ 1st Marine Division

- ^ a b "The Legend of Saint Barbara", USFAA

- ^ "St Barbara's Parade". Archived from the original on 2018-12-04. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ^ "St. Barb's festival".

- ^ "50 Year Reunion of Codelfa-Cogefar (NZ) Ltd". www.scoop.co.nz. 12 December 2017. Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- ^ Martin, John E., ed. (1998). People, politics and power stations: electric power generation in New Zealand 1880–1998. Wellington, NZ: Electricity Corporation of New Zealand. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-908912-98-8. OCLC 931064862.

- ^ Where the tradition of the 'Barbarazweig' comes from

- ^ Pfannkuch, H.O. (15 March 2013). "Medieval Saint Barbara Worship and Professional Traditions in Early Mining and Applied Earth Sciences". American Geophysical Union publication: Medieval Saint Barbara Worship and Professional Traditions in Early Mining and Applied Earth Science. History of Geophysics. American Geophysical Union. pp. 39–48. doi:10.1029/HG003p0039. ISBN 978-1-118-66539-8.

- ^ "International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences, page 38" (PDF).

- ^ "Saint Barbara's Day". Archived from the original on 2008-10-26. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ "Barbarafest 2018 – Maskenball Venedig". University of Tübingen. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ "Barbarafest 2013". Universität Freiburg. 26 November 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ fachschaft.uni-bonn. "Steinmann Student Union". Archived from the original on 2018-12-01. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Institut für Angewandte Geowissenschaften der Technischen Universität Darmstadt. (7 December 2018). "Barbarafeier am 07.12.18 im Schlosskeller". dubistgeologie.wordpress.com. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ "Tisková zpráva: Na stavbě prvního úseku metra D je vyražen první kilometr tunelů a osazena poslední soška svaté Barbory". 2 December 2022.

- ^ St. Barbara´s Cathedral, Kutná Hora

- ^ Ancient salt-works. Wieliczka see: carving by Jozef Markowski, late 19th century. (Internet Archive)

- ^ Sapeurs-pompiers de France. (4 December 2020). "Sainte-Barbe". pompiers.fr. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Information on Saint Barbara as patron of Santa Barbara, California

- ^ A Day to Honor Saint Barbara

- ^ 1850 California Stats., Chap. 15, § 4.

- ^ "Ventura County: Historical Landmarks and Points of Interest" (PDF). County of Ventura, General Services Agency. p. xiii. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ Hammond Atlas of the World. 1997.

- ^ Rodriguez, Omar. Afrocuban Religion and Syncretism with the Catholic Religion. University of Miami.

- ^ https://www.academia.edu/27429624/False_Kyiv_relics_of_St_Barbara_ False Kyiv relics of "St. Barbara" by Микола Жарких

- ^ https://www.academia.edu/44536830/Eastern_Christian_relics_in_Ukraine_in_the_late_17th_and_18th_centuries "Eastern Christian relics in Ukraine in the late 17th and 18th centuries", page 77, in the last paragraph: "St Barbara's relics were kept in Saint Michael's Cathedral in Kyiv."

- ^ http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CS%5CA%5CSaintMichaelsGolden6DomedMonastery.htm Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, "Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery": "It enjoyed the patronage of hetmans and other benefactors and acquired many valuable artifacts (including the relics of Saint Barbara..."

- ^ https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2012/07/11/149025-transfer-of-the-relics-of-saint-barbara Orthodox Church in America, "Transfer of the Relics of Saint Barbara": "The hand of Saint Barbara is kept in a special shrine at Saint Michael's Monastery in Kiev, on the left side of the church."

- ^ https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/8832019-30901 DECREE OF THE PRESIDENT OF UKRAINE №883/2019 "...1. To assign to the 19th missile brigade of the Ground Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine the honorary title "Saint Barbara" and further to name it – the 19th missile brigade "Saint Barbara" of the Ground Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine."

- ^ "Saint Barbara's Day in Georgia, December 17". Messenger.com.ge. 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- ^ "Cyprus Army notes on Saint Barbara". Army.gov.cy. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- ^ Church of St. Barbara in Varvarka Street (Moscow)

- ^ "The Legend of Saint Barbara: Patron Saint of Miners", International Society of Explosive Engineers

- ^ "THE FEAST OF SANTA BARBARA IN PATERNO'. – English NEWS". 9 December 2020.

- ^ "Festa di Santa Barbara a Paternò".

- ^ Hashwah, Hind. "How is Saint Barbara associated with a delicious dish?", Culturico, December 4, 2019

- ^ Gervers, Michael; Bikhazi, Ramzi Jibran (1990). Conversion and Continuity: Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands Eighth to Eighteenth Centuries. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. ISBN 9780888448095.

- ^ Ruben, Don (1999). World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre Volume 4: The Arab World. Routledge. ISBN 9780415865364.

- ^ Carter, Terry (2004). Syria and Lebanon. Lonely Planet. p. 66. ISBN 1-86450-333-5.

- ^ Wilhelmina and George Baramki (February 2007). "Winter Traditions in Palestine". This Week in Palestine (106). Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ "Saint Barbara: A celebration for Arab Christians". BBC.

- ^ "Barbiturates". Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ^ Kowalska, Saint Maria Faustina (2022). Divine Mercy in My Soul: Diary of Saint Maria Faustina Kowalska (3rd revised ed.). Stockbridge, Massachusetts: Marian Press. pp. 452, paragraph 1251. ISBN 978-1-59614-110-0.

- ^ "cse.dmu.ac.uk". cse.dmu.ac.uk. 2005-01-10. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- ^ Albert, Sidney P. (May 1968). ""In More Ways than One": "Major Barbara"'s Debt to Gilbert Murray". Educational Theatre Journal. 20 (2): 123–140. doi:10.2307/3204896. JSTOR 3204896.

- ^ Gan, Jessi. ""Still at the back of the bus": Sylvia Rivera's struggle". redalyc.org.

- ^ Cieslik, Emma. "Saint Sylvia's Feast Day: A Reflection on MCCNY's Tribute to a Trans Icon". Noah Becker's Whitehot Magazine of contemporary art.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Barbara". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Barbara". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

[edit]- Drolet, Jean-Paul (1990). Sancta Barbara, Patron Saint of Miners: An Account Drawn from Popular Traditions. Québec: J.-P. Drolet. OCLC 20756409.

- Graffy de Garcia, Erin (1999). Saint Barbara: The Truth, Tales, Tidbits, and Trivia of Santa Barbara's Patron Saint. Santa Barbara, California: Kieran Pub. Co. ISBN 9780963501813.

- Haas, Capistran J. (1988). Saint Barbara, Her Story. Santa Barbara, California: Old Mission. OCLC 183447944.

- Holy Great Martyr Saint Barbara: Who Was Killed by Her Own Father for Her Faith in Christ. Lives of saints, v. 5. St Marys, N.S.W.: Holy Dormition Sisterhood. 2004. OCLC 224359179.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- The Old Norse-Icelandic Legend of Saint Barbara, (Kirsten Wolf, ed.) PIMS, 2000 ISBN 9780888441348